the loving eye

notes on a painting, a friendship, and ways of seeing

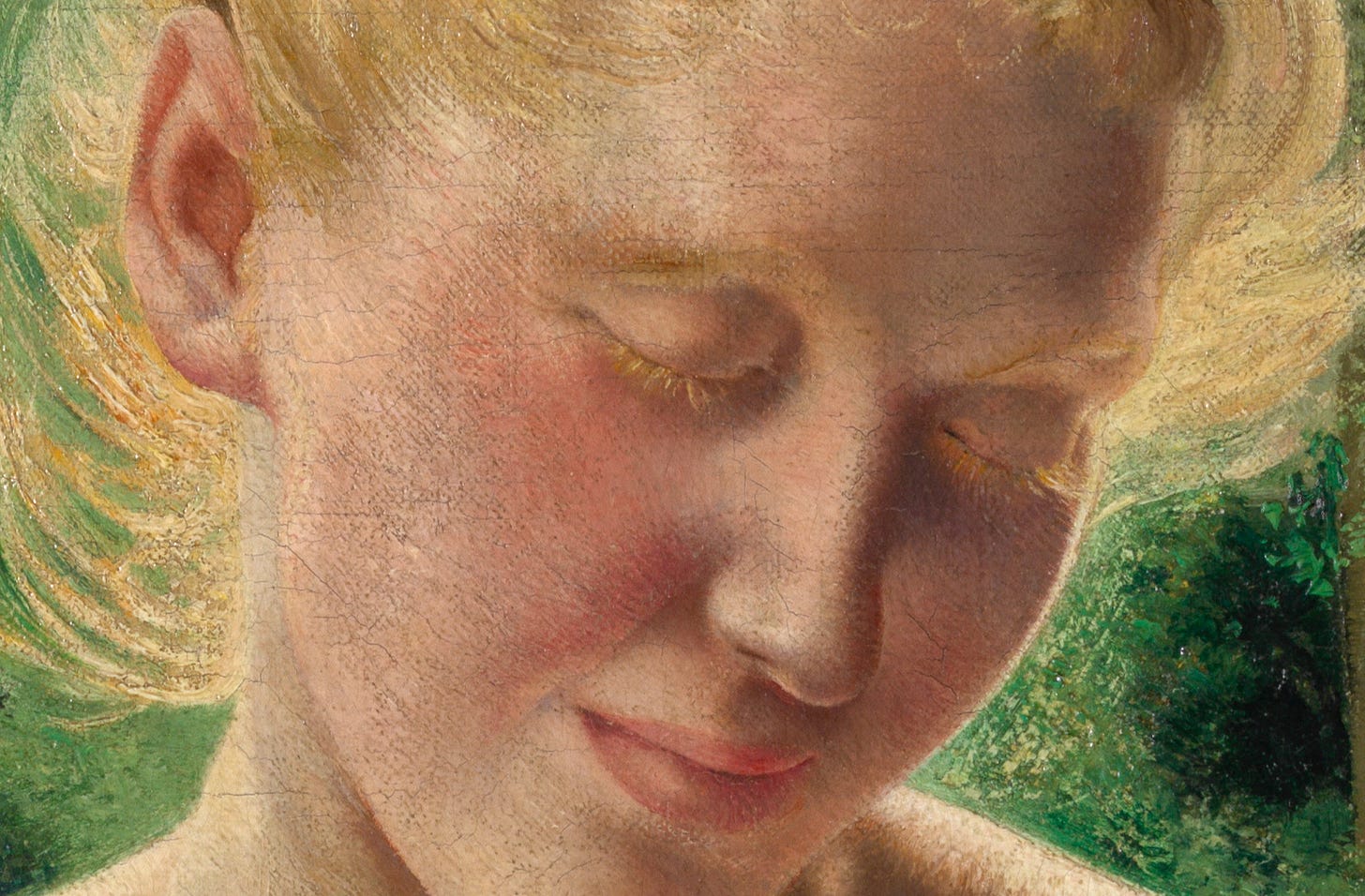

Today I want to write about this painting: Timidity, painted in 1896 by the Belgian symbolist Léon Frédéric.

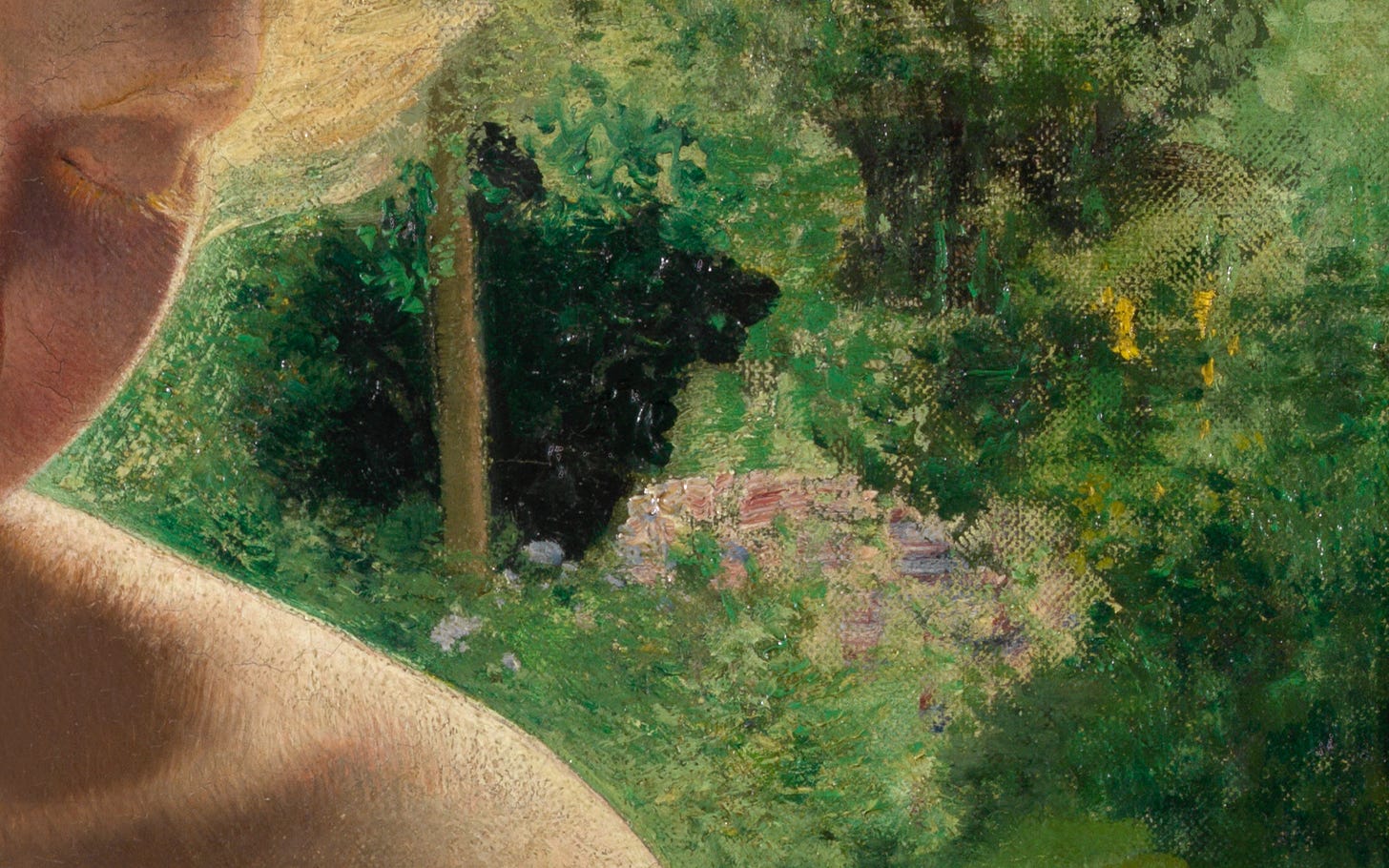

It’s a relatively unknown painting by a relatively unknown man, depicting a completely unknown and by now unknowable woman, sitting blushing and mostly nude before an impossibly green landscape. I’m writing this sitting in front of it; in front of her. Or rather, I’m taking the notes that will become what you’re reading, here in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp.

I came back here to see this painting today, over a year after she first leapt out at me from amongst all the other paintings in the room. As if a light had been switched on in the dark. Why did she catch my eye like that? There’s a lot to see here. Timidity shares her small section of wall with eleven other ornately framed paintings. The room is filled with gods and heroes, war scenes, quaint landscapes, rich women in furs. Cleopatra is here, an Amazon slaying a panther, and the mythological Leander who swam the Hellespont nightly to meet his lover Hero.

On the left, the view of Timidity is obstructed by a glass case containing a small, brightly lit statuette of Diana, the ancient Roman goddess of the hunt, wild animals, and the moon. It was carved from ivory stolen from Congo during Belgium’s brutal colonisation. On the right, she’s dwarfed by Ferdinand De Braekeleer I’s colossal painting The Spanish Fury in Antwerp, a battle scene almost five metres tall and seven wide: plundering and violence, burning houses, firing rifles, broken homeware, spears about to plunge into struggling bodies.

Timidity sits small, naked, and flushed in the middle of it all.

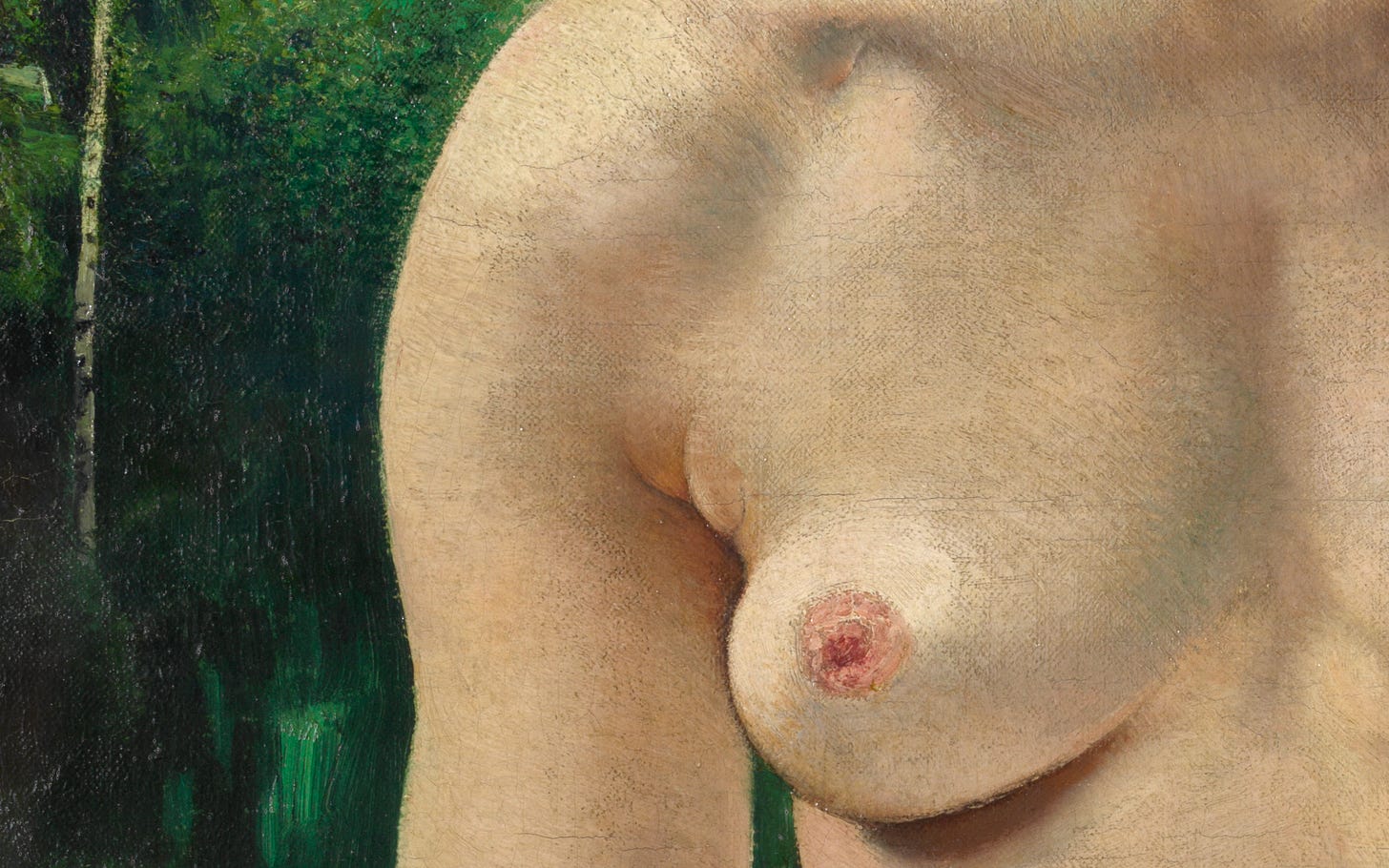

This painting is supposed to be an allegory. In symbolism, nothing is simply what it is. A naked woman with flushed cheeks averts her gaze and becomes timidity, modesty in the flesh. But calling something an allegory doesn’t undo the fact of the body. This is still a painting of a naked woman, the way there are millions of paintings of naked women, painted by men more or less like Frédéric.

Much of the European art tradition rests on this one-sided relationship: the male artist observes and depicts a nude female subject, often positioned in a passive, reclined, or seductive pose. The spectators, in those days usually also men, then observe the same female subject. The woman and her nakedness are being seen, experienced, and possessed over and over again, across centuries.

In 1972, John Berger argued in Ways of Seeing that the principal protagonist of these paintings is never actually in the painting:

“He is the spectator in front of it, presumed to be a man. Everything is addressed to him. It is for him that the figures have assumed their nudity. But he, by definition, is a stranger—with his clothes still on.”

Turning the subject into an allegory for some bigger idea or concept doesn’t make her any less naked, and it doesn’t change the dynamic. In one of the panels for his Triptych of Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation, Hans Memling depicts a naked woman looking at herself in a mirror as the embodiment of vanity. John Berger argued that, rather than vanity, hypocrisy is the real crime here:

“You paint a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, you put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure.”

So, Mr. Frédéric. You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her. You made her shyly cover herself and you called the painting Timidity, thus exploiting the nudity of the woman whose timidity you feign to admire.

Except.

There is a tenderness to this painting that is absolute and undeniable. It touches me somewhere deep, beyond the cliff of the midriff. I’m not sure the digital image really conveys its power. A few times now I’ve shown people the replica on my phone and they nod and say: nice. Or: yes, very romantic. And this is probably how you’ll see it, however you’re reading this.

In real life, though, it’s as if the painting radiates light. She’s backlit, yes, but the light doesn’t just reflect off her shoulders, her breasts, the inside of her arm: it’s as if she herself is the source of it.

There’s something about her expression, the golden eyelashes, the wisps of hair fallen from her braid. She’s looking away, pink-cheeked, hiding intimate parts of herself, which fits the allegory. But I don’t see the allegory. To me, this is a woman who has just been swimming naked in a very cold stream. Now she’s drying off, flushed from the shock of cold water, suddenly aware of the new form her nakedness takes on land. Or tired from the sun on her face, or slightly sunburnt.

I don’t see her as a passive subject, even though she’s just sitting there. I think we’re just seeing her right after the action. Her eyes are closed. She’s off in her own world somewhere. She’s not trying to seduce, not contorting her body into desirable poses. She looks content, alive. Blood rushing under her skin, warmth rising from her being.

A woman sitting naked in front of a man, closing her eyes, seemingly dreaming, drifting off. No woman I know sits naked in front of a man like this unless she feels, in some way, safe. That must be why, when I first saw this painting, I said to Adam, who was with me then: I think you could only paint this kind of portrait of someone you love.

Meeting Timidity again today, I suddenly realise the woman in the painting reminds me of my friend Sara. She has the same coppery blonde hair, the same golden eyelashes, the same flush to her complexion.

Sara and I were in middle school together. She was a year above me. We had a few friends in common, so we often found ourselves standing in the same circles in the schoolyard, our Converse-clad teenage girl feet always ever so slightly turned inward. One core memory: seeing The Ring at her house during a sleepover and being too scared to go to the bathroom alone, instead moving there in a string of terrified girls, hand in hand, shrieking at the slightest creak in the stairs, the slightest movement of the wind in the dark trees outside.

I changed schools at fifteen, and that was the last time I saw Sara. Until about three years ago, when I went to Italy for a month to focus on writing, posted an Instagram story looking for a cat sitter, and she ended up staying at my place, taking care of my cat. We quickly found each other again, bonding over good food, dysfunctional families, high school gossip, leftist politics, and the rare effortlessness of being around someone who has seen and known you at your most awkward.

Last winter, Sara was diagnosed with an aggressive type of breast cancer. In a way, she was lucky to have found out when she did. Being under 35, she’d had to beg her doctors for the screening. There wasn’t much luck involved in the rest of it. Months of chemo and other treatments. And, when the cancer proved genetic, the doctors told her she’d need a double mastectomy.

Around this time, I happened to post something about wanting to focus on photography. Sara responded with a question: would I be willing to take photos of her before her surgery? More specifically, photos of her breasts the way they were, before she’d lose them. Three days before the mastectomy, I met her in the golden hour of her kitchen.

I was so nervous. The stakes felt enormous. If these photos failed, there was no redoing them. I felt totally inadequate as a photographer, too small for the task. I’m sure she was even more nervous, considering the situation. But once we started, things didn’t feel heavy or tense at all. We laughed a lot. She rolled and lit a joint, smoked it out the window while I worked. I captured her as I saw her then, as I know her: always sitting there, in her usual spot by the window, blowing smoke into the ripening evening.

At some point Sara said that through me seeing her, and through seeing her own reflection in the open window, she was able to look at herself, really look at herself, and at her breasts, for the first time since she got sick.

I think you could only paint this kind of portrait of someone you love, I’d said. Standing here now, after having taken Sara’s portraits, I feel this in a different way.

Berger wrote that to be naked is to be oneself, while to be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognised for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object to become a nude. When I photographed Sara, I wasn’t trying to make her a nude. I wanted to catch her nakedness, which is to say: her selfhood.

In the final photographs, I don’t see breasts, or nudity, or skin, though all those things are there. Love, romantic or platonic, changes your way of seeing. It makes it more porous, more attentive. More likely to move the eye beyond the body, beyond nudity, even beyond the neatly drawn lines of who’s seeing and who’s being seen. The loving eye wants to preserve more than it wants to possess.

There’s no way to know if Léon Frédéric loved the woman in the painting or objectified her, whether he intended to turn her into a nude or simply depict her nakedness. The story, if there ever was one, has been lost or was never recorded in the first place. Which means the painting becomes a kind of empty room we can furnish with our own longing, our own narratives of intimacy and power.

I think I see love in this painting. I think that’s why it caught my eye between all these gods, angels, and heroes. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe, deep down, I’m still so much like that teenage girl who once met Sara; a child looking for love in all places.

I’m certainly not the presumed male spectator Berger described. I’m inserting myself and my interpretation into a tradition that didn’t imagine me, didn’t imagine us. Not me, the female eye, the female maker. And not Sara, the female subject asking to be depicted, to be looked at, to be made permanent; the co-collaborator in her own image-making. This is a new tradition, one I want to continue writing. One loving look at a time.